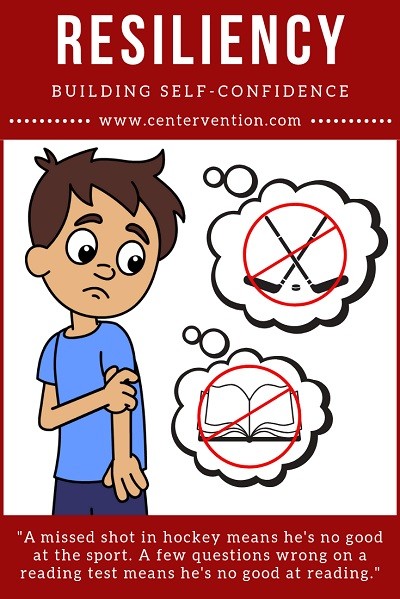

Q: My son is a smart, capable boy, but he is lacking self-confidence in just about anything he does. A missed shot in hockey means he’s no good at the sport. A few questions wrong on a reading comprehension test means he’s no good at reading. I tell him he’s a great kid all the time, but he just doesn’t seem to be confident in anything he does—and he’s starting to display little interest in trying something new.

How can I help him build his self-confidence?

Lacking self-confidence is a problem for many kids

Frequent testing in school keeps their focus on the grade, not the material. Pressure to win a spot on a travel sports team or a competitive dance program can take away the fun of an after-school pursuit. And, in their free time, they’re bombarded with images of unattainable beauty and perfection on their phones and tablets.

Some kids, of course, thrive as they work to meet these sky-high expectations. But others worry that they’ll never get anything right, and their self-confidence—the trust they have in their own abilities and judgements—can flounder. It’s no wonder that kids face higher levels of mental health issues than ever before. More than 8% of kids ages 6 to 17 have been diagnosed with either anxiety or depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But self-confidence is a vital quality for a developing effective interpersonal skills. Self-confident people live with less fear and anxiety, are more motivated and resilient and enjoy more fulfilling relationships and a stronger sense of self, writes Barbara Markway, a clinical psychologist and author of “The Self-Confidence Workbook,” on Psychology Today.

“Self-confidence doesn’t mean you won’t sometimes fail,” she writes. “But you’ll know you can handle challenges and not be crippled by them.”

Self-esteem versus self-confidence

U.S. parents, however, seem to place more emphasis on building up their child’s self-esteem—how they feel about their own worth or abilities—than their self-confidence, said Melissa DeRosier, clinical psychologist and CEO of 3C Institute.

“Self-confidence and self-esteem are not the same thing,” DeRosier said. “I can have very high self-esteem, but feel very incompetent and not able to handle things, especially if something happens that doesn’t go the way I wanted it. … The emphasis on always having children feel good about whatever they’re doing is actually undermining their self-confidence.”

DeRosier’s recommendation to parents who want to boost their child’s self-confidence may seem counter-intuitive in a world that focuses on making sure kids feel good about themselves, but, she said, it works. Parents, she said, must encourage and embrace opportunities for their kids to fail.

“Parents, too frequently, try to protect their child from any kid on failure—socially, academically, on the ballfield, wherever,” she said. “If you don’t learn to deal with failure, … it actually is making you increasingly vulnerable because, at some point, you will. No one goes through this life charmed.”

DeRosier recommends that parents offer their kids regular opportunities to lose, such as playing board games together. After they lose a game, said DeRosier, have a discussion with them about the experience. Ask them what they learned and how they’ll use those lessons the next time. “The main thing about self-confidence is understanding that I can deal with it no matter what,” she said.

Given them grace

Jennifer Miller, an expert in social and emotional learning and author of “Confident Parents, Confident Kids,” offers up another strategy for parents: Create a culture of learning in your family. Young children often are engaged in all kinds of messy activities—whether that’s smashing their massive block tower instead of neatly disassembling it and putting the blocks away or drawing on the walls with permanent markers.

“If they feel ashamed when they make a mess or have accidents, then they begin to get the message that their learning is limited and it is not fully permitted,” Miller said. “That doesn’t mean that adults don’t get stressed out or upset when there are Sharpie markers on the wall. That happens.”

But, instead of getting visibly upset, take a break and wait to talk with them until after you’ve calmed down. “No matter what age and stage, we are all learning,” she said. “And we have to give each other grace in that process.”

Track their success

“Start tracking the good things your child does by creating a Success Journal. Every time your child does something ‘good,’ write in the journal. Then, any time they are getting down on themselves, pull it out and have them read through past accomplishments.”

Danny Strecker in his book, How to Double Your Child’s Confidence in Just 30 Days

Let them explore

“Confidence is created out in the real world—not at home sitting on the couch. It is imperative to give children healthy and safe opportunities to play in and explore their worlds so they can gain a sense of trust in themselves. Self-trust is the ability to rely on one’s own inclinations (thoughts, feelings and instincts) first, regardless of what others are saying or doing. It is also crucial as a parent to instill in your child a sense of self-trust, optimism and avid faith in his or her ability to navigate new situations because soon that faith is internalized. Self-trust and self-reliance are necessary ingredients to inner confidence.”

Maureen Healy, child development expert and author, in her book Growing Happy Kids: How to Foster Inner Confidence, Success and Happiness

Focus on the process

“Do your best to shift your dialogues from the end results to the process for your kids. Instead of focusing only on the ‘A’ he earned on the spelling test, talk about how he studied and prepared for it. Instead of showering praise for your child’s score in the game, talk about how all the practice and perseverance paid off. When kids focus on the process – how they can get to the end products rather than the final outcome itself, they still enjoy the highs from the wins, but don’t worry quite so much about the lows and they’ll be less dependent on others for approval.”

Amy McCready, author of The ‘Me, Me, Me’ Epidemic, via A Fine Parent